DNA Test

Confirmed medical conditions:

Current medications:

My Clinic:

This Breed of does not have any documented genetic predisposition to a specific disease at the current time. This does not necessarily mean that this breed does not have any genes predisposing to a certain disease, but instead this may be due to the fact that it is a relatively new or rare breed, and/or there has been insufficient collection of data to document such predisposition to date. We continue to monitor all breeds for the emergence of patterns of disease occurrence, and it is always a good idea to speak to your veterinarian and/or breeder regarding any disease that may occur in your pet. Remember, just because a disease may be more common in certain breeds, does not mean your pet will go on to develop this disease - we are referring to average likelihoods only.

Below we have outlined some of the most common diseases that occur in more generally

| Disease | Estimated Prevalance | Result |

|---|---|---|

|

Alopecia X (Adrenal Sex Hormone Dermatosis) |

No prevalence data is currently available

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

No routine screening is available prior to the development of clinical signs.

Overview

This condition seems to have become more common as breeders have actively selected for a thick hair coat, and is seen most commonly in breeds such as the Pomeranian, Samoyed and Siberian husky. Hair follicles have receptors for sex hormones, and these receptors can convert one sex hormone to another. Adrenal sex-hormone imbalance can occur in intact or desexed males and females, and is thought to be related to an excess level of ACTH production acting on the adrenal gland.

Signs develop in young adult animals, with a bilaterally symmetrical alopecia (i.e. hair loss that is the same on both sides of the body) and usually with increased pigmentation of the skin. Primary hairs are lost first, then secondary hairs. This is a similar pattern to the hair loss seen in other hormonal alopecia (collectively called endocrine alopecia), for example a dog with hypothyroidism may develop similar signs, but usually this will be seen later in life (middle age). Dogs with loss of primary hairs but still with an undercoat may have a “woolly” appearance. This occurs especially in the Arctic Circle breeds.

Diagnosis is by skin biopsy and measuring adrenal sex hormones before and after giving ACTH. Often progesterone and 17-hydroxyprogesterone are elevated, but many other hormones can also be elevated, including testosterone, androstenedione, 17B-oestradiol and dehydroepiandrostenone. The treatment of choice for intact animals is desexing. This will be curative in some cases. In others signs may return after a period of time with a normal coat. For desexed animals or those that do not respond to desexing, anti-corticotrophic medications (e.g. trilostane, mitotane) or melatonin may be tried. Side effects vary but certainly can occur. It is important to protect affected animals from extremes of temperature (hot and cold) as well as wind. Otherwise the condition should not affect their overall health. |

||

|

Congenital Portosystemic Shunts. |

No prevalence data is currently available

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. Paired bile acid testing; can perform at 8 weeks in breeds where there is a high prevalence. In other predisposed breeds consider screening any undergrown pups or pups with any suggestive signs.

Overview

This is a condition where the blood vessels that run from the gastrointestinal tract to the liver have developed abnormally, and the liver is bypassed to a varying degree. Blood from the gut runs directly into the central circulation that flows to the heart, and this bypasses the detoxifying effect that the liver normally carries out. The liver is also responsible for taking nutrients from this blood and metabolising them into products that the body needs. Congenital portosystemic shunts (i.e. developmental abnormalities from birth) are thought to be hereditary to some degree, as distinct breed predilections are seen. The mechanism for this inheritance has only been established for a couple of breeds to date.

Signs can vary from small, poorly grown pups to non-specific gastrointestinal signs (such as vomiting and diarrhoea). Urinary tract signs due to the presence of ammonium biurate crystals may also occur, and in severe cases neurologic signs develop due to a build up of toxins in the blood. Dogs may then seem blind, circle, head press or seizure. Dogs with congenital portosystemic shunts are usually diagnosed before the age of 2 years, with many being picked up as puppies. However, milder shunts may not be picked up until later in life.

Diagnosis is usually by blood tests, including fasting and post-prandial (post-meal) bile acids. Further tests are available if required. Shunts may be inside or outside the body of the liver, and the location of the shunt also needs to be determined if surgical correction of the shunt is to be attempted. This can be done via a number of imaging techniques. Most shunts can be corrected surgically, and if surgery is uncomplicated dogs will do well without requiring further medication or dietary management. Medical treatment with medications, antibiotics and dietary modification are largely aimed at reducing the toxin load within the blood, to reduce/prevent hepatic encephalopathy (neurologic signs such as seizures).

Congenital portosystemic shunts that occur in predisposed breeds are generally of a surgically treatable nature, while those that occur sporadically in unrecognised breeds are often more inaccessible to surgical correction. |

||

|

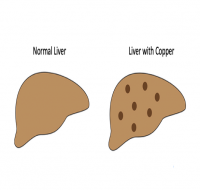

Copper Hepatopathy |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. Liver panel (including ALT, AST, AP) at least annually from 1 year of age if in a high risk breed.

Overview

This is a disease associated with the liver that results in liver inflammation and damage, with scarring and gradual loss of liver function. The disease is associated with a primary defect in copper metabolism and/or excretion of copper into the bile. This leads to copper accumulation in the liver cells, which is toxic to the cells, and eventually leads to cell death. Inflammation and scarring are secondary to death of the liver cells. This condition has an increased prevalence in several breeds, and is most common in the Bedlington terrier, in which the disease appears to be transmitted as a recessive trait. The condition results in a slowly progressive liver disease that typically first shows itself in the young adult. Jaundice is not usually seen until late in the disease process. In the West Highland white terrier, accumulation of copper generally occurs early in life, but copper levels may level out between normal levels and those that result in clinical disease. These dogs have elevated liver copper levels, but do not necessarily become clinically ill with liver failure. Once copper levels accumulate to levels that damage enough liver cells to cause signs of liver disease, then signs such as excessive drinking, mild weight loss and inappetance may be seen. As more liver mass is destroyed, weight loss becomes worse and abdominal swelling may be seen. Inappetance increases and vomiting, diarrhoea and jaundice develop. Diagnosis is based on blood tests, a liver biopsy and liver copper levels. Young dogs in a predisposed breed should be screened for elevation in liver enzymes regularly, and constant elevation is worth investigating further. The disease cannot be cured, but is managed with dietary changes and medications. |

||

|

Entropion |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. Routine part of puppy examination at approx 8-12 weeks of age.

2. Carry out recheck at 6-7 months.

Overview

This refers to eyelid/s that are turned inward towards the eye, so that the eyelashes or edge of the eyelid rub on the cornea. This can result in rubbing, corneal erosion, scarring, vascularisation and even corneal ulceration, which is painful and if untreated can lead to blindness. Entropion of the lower lid is the most common type seen, but sometimes rolling in of the eyelids is seen in the upper lid, at the medial canthus of the eye (both eyelids) or at the lateral canthus of the eye (both eyelids). Entropion develops due to the conformation of the head, selection for excess skin folds, the size of the eyes and the size of the eyelids, and is thought to have a polygenic (complex) mode of inheritance.

Signs of entropion include tearing, reddening of the eye/s and conjunctiva, squinting and sensitivity to light, and possibly a purulent discharge. Infection is usually secondary to damage by rubbing of the lid edge on the sensitive structures of the eye. Entropion may be present from as early as 2-4 weeks of age, but is more commonly seen at 4-7 months. It is worth noting that pain from corneal ulceration or infection will cause a spastic entropion, which will worsen the apparent rolling in of the eyelid.

In pups, temporary relief is often produced by placing stay sutures to hold the eyelids away from the surface of the eye (often called “tacking”). Once the eye and head reach adult dimensions, between 6 - 12 months of age, final surgery is performed to correct the entropion. Surgery to correct entropion is quite complex, and sometimes a second surgery is required to obtain a correct sit of the eyelid. It is recommended affected animals are not used for breeding. |

||

|

Epilepsy (Idiopathic, Primary or Inherited Seizures) |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

No screening currently available - thorough work up of all cases of seizure recommended.

Overview

Epilepsy is a disease characterised by seizures, and is diagnosed by ruling out all possible reasons or causes for seizures – causes such as disease or trauma to the brain, metabolic disease (such as low levels of glucose or calcium in the blood), or exposure to toxins. When no cause for seizures is present, this is called primary or idiopathic seizures - or epilepsy - and is generally accepted to have a genetic basis. The precise method of inheritance is not known, but is suspected to be recessive and affected by several genes.

Epilepsy generally presents between 1.5 and 3 years of age, although it may be seen between 6 months and 5 years. Dogs whose seizures begin at less than 2 years of age are more likely to have severe disease that is more difficult to control.

Seizures are almost always generalised, or “grand mal” type, and will begin initially as a single seizure followed by recovery. Also called “tonic-clonic” seizures, there is a period where the dog goes stiff and falls (if standing), followed by a variable period of repeated muscle contractions (jaw chomping, legs jerking). Salivation occurs and loss of bladder and/or bowel control may also occur. The seizure will last up to a minute or two, followed by a variable recovery period.

Epilepsy cannot be cured, and a dog will continue to suffer seizures for the rest of its life. Seizures tend to occur more and more frequently if the condition is left untreated, and can be fatal in severe cases. Treatment is with anti-seizure medication (anticonvulsants), and aims to reduce the occurrence and severity of seizures. |

||

|

Exposure Keratopathy (Corneal Ulcers) |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

No screening possible - owner education and vigilance essential.

Overview

Corneal ulcers occur commonly in certain breeds due to the conformation of their head and eyes. When the eyes are particularly prominent they are very prone to traumatic injury. The eyelids may not fully close over the entire front of the eye, which can cause dryness of the cornea. This can especially occur at night, when a dog is asleep. Drying of the cornea can cause surface irritation and pain, and rubbing can then cause more damage and lead to ulceration of the cornea.

In addition to this, many affected breeds are small dogs, which means that their eyes are constantly exposed to objects such as grass and bushes that may cause damage to the eye. When the eyes are more prominent, they are more prone to encounter foreign objects when a dog is playing, or just out for a walk.

Corneal ulcers are not only painful, they are prone to infection, and if not treated promptly can lead to inflammation spreading within the eye. This can cause further pain and blindness due to secondary glaucoma (pressure increase inside the eye). The owner needs to vigilant for any injury or irritation of the eye, and ensure that prompt veterinary treatment is obtained for any eye problem that may arise. Treating corneal ulcers at home is not only unlikely to be successful, but many “home remedies” may actually cause more irritation and damage.

Surgery for dogs with prominent eyes is ultimately curative - the eyelids are sutured together at the medial canthus (inner margin) to make the opening of the eyelids smaller. This means the surface of the eye is covered more fully by the eyelids when they close, and the surface of the eye is not so prone to drying out.

Corneal ulcers can also be caused by several common eye conditions, such as entropion (where the eyelids are abnormally turned inwards and rub on the cornea) and “dry eye” (or keratoconjunctivitis sicca) where there is a reduction in tear production, leading to drying and ulceration of the cornea. These conditions are seen commonly in a number of dog breeds. |

||

|

Hypothyroidism |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. Consider TgAA at 1, 2, 3, 4 & 6 years (generally used in pure breed breeding certification programs).

1. Thyroid panel - ie baseline Total T4 & TSH. (Run tests in a “well” dog) - recommend annually from two years of age.

Overview

Hypothyroidism is the most common endocrine (hormonal) disease in dogs, and most commonly occurs due to an immune-mediated process where the immune system destroys the thyroid gland (called lymphocytic thyroiditis). It is thought that the end stage of this immune-mediated destruction is an atrophied, fatty thyroid gland.

Hypothyroidism is a complex and progressive disease that is often not diagnosed until signs are well progressed, as early signs are non-specific and can vary widely. They may consist (in the younger adult dog) of vague signs such as reduced energy levels, or increased susceptibility to infections. Most veterinarians and owners do not test for this disease every time a relatively young dog gets an infection! Also, when an animal is unwell, their thyroid hormone level is likely to be low regardless of how healthy their thyroid gland is, (called "sick euthyroid syndrome") which further complicates attempts to get an early diagnosis.

Late stage (advanced) signs of disease such as bilateral symmetrical alopecia (hair loss on both sides of the body), weight gain, poor cold tolerance and failure of clipped hair to regrow are more recognisable to the owner and veterinarian as signs of serious illness, although these signs are generally not seen until middle age or later. These signs will generally lead a veterinarian to test for hypothyroidism.

In almost all breeds there is currently no DNA test for hypothyroidism, however there are recent improvements in screening tests, and in countries such as the UK and USA there are breeding certification programs for hypothyroidism (e.g.; Orthopedic Foundation for Animals Hypothyroidism Certification Program - see http://www.offa.org)

The OFA program bases certification on the thyroid hormone level test (fT4 and TSH), as well as a test for antibodies against thyroglobulin (TgAA), which is a good indicator for lymphocytic thyroiditis. Testing as young as 1 year of age can pick up this disease, and certification for breeding can be provided, although re-testing at 2, 3, 4 and 6 years is recommended for dogs testing normal at 12 months. It is strongly recommended that affected dogs not be used for breeding.

Treatment of hypothyroidism is with daily hormone replacement using a synthetic thyroid hormone. This aims to maintain approximately normal levels of thyroid hormone within the animal. Lifelong treatment is required, and if maintained, dogs will generally lead a normal, healthy life. |

||

|

Inherited Deafness |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. Standard examination and hearing testing at puppy examination prior to sale (8-12 weeks of age)

2. Consider BAER testing. Overview

Predominantly white, merle or piebald colouring predisposes dogs to inherited deafness. Deafness in linked to the gene/s associated with producing these colourings in dogs, and deafness is strongly heritable. Affected animals may be deaf in one ear or both ears. Pups are not born deaf, but will start to lose their hearing at around 3 - 4 weeks of age, and will be completely deaf a few weeks to months later.

Diagnosis can be established using standard hearing tests when a puppy visits the vet for their puppy vaccinations, and definitively established by conducting a brainstem auditory-evoked response (BAER) test if necessary (this is a specialist veterinary procedure).

A dog that is deaf in one ear can still be a good pet, although he should be desexed to prevent breeding. BAER testing is generally required to detect unilateral deafness accurately. A dog that is bilaterally deaf (deaf in both ears) will generally not make a good pet, as he will be easily startled and difficult to train. There is no treatment available for inherited deafness. |

||

|

Renal Dysplasia |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. Kidney ultrasound may be used if high incidence of the disease seen in certain lines - screen prior to breeding (e.g. at 6 months)

2. Urinalysis and blood tests (include urine protein creatinine ratio) – test annually for diagnosis as early as possible.

3. DNA test is available

Overview

Renal dysplasia is an inherited condition that occurs when there is abnormal foetal development of the kidneys. There is a persistence of immature filtering structures (glomeruli) after birth and into adult life. Also, glomeruli are lost and replaced by fibrous (scar) tissue as time progresses. Glomeruli are the part of the kidney that filter fluid to help form urine, and once around 70 – 75% of glomeruli are lost or are not working properly, renal failure is the result. Renal dysplasia is seen in a number of breeds, and is most commonly seen in the Shih Tzu, which has an estimated incidence of up to 85% in the breed. The number of clinical cases, however, remains low.

Recent research has narrowed down the genetic abnormality and researchers believe the defect to be a dominantly inherited trait with variable penetrance. Penetrance is thought to be quite low, and this helps to explain why some puppies die at a young age from renal failure, while many other dogs may also have the disease but not show clinical signs until late in life, or not at all. It also explains why dogs that have no clinical signs of renal disease can produce offspring with renal dysplasia and early renal failure.

Renal failure can occur as young as 3 – 6 months of age, and when this happens, blood and urine tests can easily diagnose chronic renal failure. Signs most often develop before 2 years of age, but can be seen later in life. Glucosuria (glucose in the urine) is sometimes seen in some breeds; however proteinuria (protein in the urine) is a more common finding. Diagnosis of renal dysplasia may be suspected on kidney ultrasound but is generally made by examination of a wedge biopsy of kidney and identifying foetal glomeruli in the kidney tissue. There is a DNA test for some breeds.

Signs of kidney failure include increased thirst and increased urination, weight loss, decreased appetite and as the disease progresses, vomiting, bad breath (due to toxins building up in the bloodstream because they are not being excreted by the kidneys anymore), mouth and gastrointestinal tract ulcers, anorexia and possibly diarrhoea. There is no cure for renal dysplasia, and once a dog is showing signs of chronic renal failure they have already lost almost three quarters of their functioning kidney. Medications and dietary changes are used to try to manage the signs of the disease, but ultimately dogs will need to be euthanased due to their deteriorating health. |

||

|

Sebaceous Adenitis |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

No screening is available in breeds other than the standard Poodle.

Overview

This is a collection of inflammatory skin diseases that affect the hair follicles, and in particular seem to lead to destruction of the sebaceous glands, which line the hair follicle. Many breeds are affected, and in general there are two “classes” of disease, type I, which is generally seen in seen in long haired breeds, and type II, most often seen in short haired breeds. However, some overlap exists and treatment should be based on individual response.

Most dogs are affected in young adulthood, when hair becomes dull and brittle, and patchy areas of hair loss develop. They may also develop scale, which can be severe in some cases. Lesions often start along the dorsal part of the head and body. There may also be a secondary bacterial infection of the hair follicles, seen as small pustules (or “bumps”). Self trauma may make lesions worse.

In long haired breeds the condition generally progresses rapidly, and only responds to symptomatic treatment. In contrast short haired breeds generally have a slowly progressive disease that responds best to therapy with retinoids and cyclosporine. Diagnosis of sebaceous adenitis is by skin biopsy, and these biopsies need to be assessed by a recognised veterinary dermatopathologist. |

||

These conditions are reported to have a breed predilection in the Mixed Breed, although they are less common than those mentioned earlier, or have less of an impact on the animal when they occur. Hence they are not covered in detail in this article, however further information can be found by clicking on any diseases that are highlited. This list is not a comprehensive list of all diseases Unknown may be prone to.