DNA Test

| Category | POSITIVE | CARRIER | CLEAR |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ophthalmologic - Associated with the eyes and associated structures |

1 |

- |

- |

|

Urinary system / Urologic - Associated with the kidneys, bladder, ureters and urethra |

- |

- |

- |

|

Immunologic - Associated with the organs and cells of the immune system |

- |

- |

- |

|

Metabolic - Associated with the enzymes and metabolic processes of cells |

- |

- |

- |

|

Musculoskeletal - Associated with muscles, bones and associated structures |

- |

- |

- |

|

Nervous system / Neurologic - Associated with the brain, spinal cord and nerves |

1 |

- |

- |

Endocrine - Associated with hormone-producing organs |

- |

- |

- |

|

Cardiovascular - Associated with the heart and blood vessels |

- |

- |

- |

|

Haemolymphatic - Associated with the blood and lymph |

- |

- |

- |

|

Digestive system / Gastrointestinal - Associated with the organs and structures of the digestive system |

- |

- |

- |

|

Dermatologic - Associated with the skin |

- |

- |

- |

|

Reproductive - Associated with the reproductive tract |

- |

- |

- |

|

Respiratory - Associated with the lungs and respiratory system |

- |

- |

- |

|

Trait (Associated with Phenotype) |

- |

- |

- |

Confirmed medical conditions:

Current medications:

My Clinic:

This Breed of does not have any documented genetic predisposition to a specific disease at the current time. This does not necessarily mean that this breed does not have any genes predisposing to a certain disease, but instead this may be due to the fact that it is a relatively new or rare breed, and/or there has been insufficient collection of data to document such predisposition to date. We continue to monitor all breeds for the emergence of patterns of disease occurrence, and it is always a good idea to speak to your veterinarian and/or breeder regarding any disease that may occur in your pet. Remember, just because a disease may be more common in certain breeds, does not mean your pet will go on to develop this disease - we are referring to average likelihoods only.

Below we have outlined some of the most common diseases that occur in more generally

| Disease | Estimated Prevalance | Result |

|---|---|---|

|

Cataract (Cloudiness of the Lens of the Eye) |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. DNA test if available for the breed - screen breeding animals prior to entering into a breeding program

– NB available currently for Australian shepherd, French bulldog, Boston terrier, Staffordshire bull terrier (juvenile form), miniature American shepherd

2. Eye examination by veterinary ophthalmologist; recommended as part of puppy eye exam, then annually (may be required for breeding certification).

Overview

Most cases of cataract in dogs are of an inherited form. This disease causes cloudiness in the lens of the eye. This cloudiness may be located in the centre of the lens, or towards the front or the back of the lens. Inherited cataract is almost always bilateral (that is, in both eyes).

The disease can become apparent over a wide range of ages, ranging from when the puppy first opens its eyes to around 6-8 years of age. Cataracts that develop at or around birth are termed congenital cataract. Those that develop in dogs under 2 years of age are called juvenile cataract, while those developing in dogs between 2-6 years are termed adult onset cataract. Those that develop in dogs older than 8 years are generally not of an inherited nature, and may sometimes be due to other disease (e.g. diabetes mellitus).

Cataract may also progress (get worse) at varying rates, resulting in initial blurred vision which may often progress to complete blindness. Some cataracts may progress very rapidly. It also may not progress much at all, and this is termed static cataract. Congenital cataracts may be static in nature or they may progress. They may be inherited, or may be secondary to other inherited defects (e.g. persistent pupillary membrane or persistent hyaloid artery) or secondary to in utero infections, toxicities or other foetal trauma.

Cataract is diagnosed by eye exam once it is present in the lens, and by ruling out other causes. There are DNA tests available for the inherited form of cataract in some breeds. Most cataracts can be treated surgically, and the earlier this is performed the better the prognosis is, and the less chance there is for complications. An intraocular replacement lens is often placed, which helps improve post-surgical vision.

Breeding programs in breeds where cataract is a major concern should involve ensuring parents are clear by screening. Most areas will have a recognised registration program for inherited eye diseases, which is strongly recommended for breeders to participate in. In Australia, the Australian Veterinary Association runs the Australian Canine Eye Scheme (ACES), while breeders in the USA can certify their dogs via the Canine Eye Registration Foundation (CERF).

Cataract can also be associated with other diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, and hypocalcaemia, and also due to some toxins, including internally produced toxins (e.g. those produced due to retinal degeneration) as well as external toxins. Cataract associated with diabetes mellitus often progresses very rapidly.

Cataract should not be confused with the normal aging change of the lens of the eye called sclerosis – this is often visible as a white cloudiness in older dogs’ eyes. Often this can be confused with cataract by dog owners, but sclerosis of the lens does NOT cause loss of vision. |

||

|

Elbow Dysplasia |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. Recognized radiographic screening technique under general anaesthesia at 12 - 24 months of age (usually done at same time as hip dysplasia screening) and assessed by accredited radiologist (may be required for breeding certification).

Overview

Elbow dysplasia refers to a group of developmental disorders affecting the elbow and leading to forelimb lameness in large breed dogs. It is inherited, and has a high heritability, with certain breeds showing increased prevalence of the disease.

One or more of the following abnormalities may be seen in either one or both elbows of affected animals: Ununited anconeal process (UAP) Fragmented medial coronoid process (FCP) Osteochondrosis of the medial humeral condyle (osteochondritis dissecans, or OCD, occurs once a cartilage flap forms in the joint) Incongruity due to asynchronous proximal growth of the radius and ulna Incomplete ossification of the humeral condyle

Elbow dysplasia is one of the most common causes of forelimb lameness in large breed dogs. Onset of joint pain is usually between 4 - 12 months, with lameness made worse following exercise. Some dogs may not show pain and lameness until later in life, when degenerative joint changes and arthritis becomes apparent. Diagnosis is confirmed with x-rays, and screening and scoring is performed for registries (e.g. the OFA Elbow Registry in the USA) for breeding animals in many countries.

Treatment depends on the type of abnormality that is present. FCP is the most common form of elbow dysplasia in dogs, and for this form of the disease medical management is usually recommended, as surgical treatment has not been shown to improve the outcome for the patient. Other forms of elbow dysplasia regularly seen, OCD of the elbow and UAP, are recommended to be treated surgically to obtain the best outcome, and the prognosis is good if surgery is performed as early as possible, before any bony joint change (e.g. arthritis) occurs. |

||

|

Epilepsy (Idiopathic, Primary or Inherited Seizures) |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

No screening currently available.

Note: EEG may be of some benefit to screen familial lines with a particularly high incidence of the disease. Testing at or before 1 year of age recommended, exclude affected animals from breeding.

Overview

Idiopathic epilepsy (IE) is a disease characterised by seizures, and is diagnosed by ruling out all possible reasons or causes for seizures - causes such as disease or trauma to the brain, metabolic disease (such as low levels of glucose or calcium in the blood), or exposure to toxins. When no cause for seizures is present, this is called primary or idiopathic epilepsy - and is generally accepted to have a genetic basis, although the mechanism by which it is inherited is not yet understood. Often the name is shortened to epilepsy in general conversation. Research suggests an autosomal recessive mechanism of inheritance with incomplete penetrance, and influence from moderator genes.

Epilepsy generally presents between 1.5 and 3 years of age, although it may be seen between 6 months and 5 years. Dogs whose seizures begin at less than 2 years of age are more likely to have severe disease that is more difficult to control.

Seizures are almost always generalised and symmetrical (as opposed to just one side of the face twitching, for example, which is called a partial seizure), and will begin initially as a single episode. Also called a “tonic-clonic” seizure, the dog initially goes stiff and loses consciousness, followed by a period of repeated severe muscle contractions. Salivation occurs and loss of bladder and/or bowel control may also occur. The seizure will last up to a minute or two, followed by a variable recovery period. Clusters of seizures or continuous seizuring - known as “status epilepticus” - may occur as epilepsy progresses (gets worse) over time.

Idiopathic epilepsy is generally a diagnosis of exclusion - this means all other causes of seizures are excluded as possible causes. There are some changes that can be detected that do support a diagnosis of epilepsy. CSF analysis of epileptic patients may show that levels of the neurotransmitter GABA are reduced, while levels of glutamate are elevated. Electroencephalography (EEG) shows unique and consistent patterns in dogs with primary inherited epilepsy, and may be used to detect epilepsy before 1 year of age. Currently, with no DNA test available, this is the most promising screening test for familial lines with a high incidence of the disease seen previously.

Epilepsy cannot be cured, and a dog will continue to suffer seizures for the rest of its life. Seizures tend to occur more and more frequently over time if the condition is left untreated, and also tend to worsen in their severity. Seizuring can be fatal in severe cases, such as when a patient goes into status epilepticus. Treatment is with anti-seizure medication (anticonvulsants), and aims to reduce the frequency and severity of seizures, and to improve the dogs' quality of life. Dogs with epilepsy should not be used for breeding. |

||

|

Exercise Induced Collapse |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

DNA test available for dynamin-1 mutation, recommend screen all breeding animals by 1 year of age.

Overview

This is an autosomal recessive condition that affects Labradors, as well as several other related breeds. The condition is also seen in mixed breeds, mainly Labrador crosses. The condition is not common, although it is estimated up to 35% of the Labrador population (in the USA) may be carriers of the gene mutation that causes the disease (ie mutation of the dynamin-1 gene). Signs are usually first seen in young adults, between 6 months and 3 years of age. With vigorous exercise lasting 5-20 minutes, a loss of control becomes apparent in the hind limbs. Starting as a wobbly gait, the loss of control progresses to collapse, and sometimes dogs may seem confused. Occasional deaths have been reported, so it is important that exercise is stopped as soon as signs first appear. Excitement and high temperatures and/or humidity may exacerbate signs. There are sporadic reports of various supplements having some positive effect in a small number of dogs, as well as one report of sub-anticonvulsant doses of phenobarbitone being useful in some severely affected dogs; however there is currently no proven reliable cure or treatment for this disease. All affected animals should be withdrawn from work and should avoid situations involving excitement and/or stress. |

||

|

Hereditary Myopathy (Autosomal Recessive Muscular Dystrophy) |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. DNA testing is available in Labrador retrievers and screening should be considered for breeding animals prior to entering a breeding program (eg at 1 year of age).

Overview

This is a rare inherited disease of Labrador retrievers which causes muscle weakness due to a lack of type II muscle fibres. The first sign in a puppy with this disease is a bunny hopping gait, which by around 5 months of age has progressed to generalised weakness and stunted growth. The muscles become atrophied (shrunken) although the dog remains bright and alert mentally. The condition usually stabilises by 6 – 8 months of age.

Severely affected dogs are much debilitated, however more mildly affected dogs may have a good prognosis for a quiet life. There is no cure for hereditary myopathy, and because the disease is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait, affected animals should not be bred, and both parents will be carriers, as will siblings – these animals also should not be bred. |

||

|

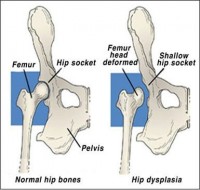

Hip Dysplasia. |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

Recognised radiographic screening technique under general anaesthesia at 12 - 24 months of age and assessed by accredited radiologist (may be required for breeding certification).

Overview

Hip dysplasia is a developmental problem of the hip joint that causes “loose” hip joints (hip joint laxity) and leads to degenerative joint disease (arthritis). It occurs in many dog breeds, and there is a genetic predisposition to develop this condition, but the mode of inheritance is complex, and involves many genes (polygenic). Development of the disease is also influenced by environmental factors as well as body size and conformation, with larger dogs having a higher incidence of the condition, including many breeds that are heavily built. Because of the complexity of the genetics associated with canine hip dysplasia, normal parents can still produce affected offspring.

Hip dysplasia can be painful as early as 5-10 months of age, and affected dogs may have trouble with walking up stairs, or show stiffness after exercise. It is more common that no signs are seen when the dog is young, but pain develops as the dog gets older. This is because the hip joint is loose, and the bony structure of the joint becomes altered in an attempt to compensate and stabilise the joint. This is known as arthritis, and it causes pain and restriction of movement of affected joints. Pain can become very severe or crippling as the dog ages and as arthritic changes become ever more severe.

Often this joint pain will be worse in cold weather. Keeping your dog at a healthy weight, providing gentle or non-weight bearing exercise (e.g. swimming or walking in chest-deep water) and a warm, padded bed at night can all help with arthritic pain, as well as several supplements and medications that your vet may prescribe to aid in joint repair and to provide pain relief. Installing ramps in place of steps at home is another great way to help your arthritic dog, as is placing food and water bowls where they can be easily accessed and providing a warm coat in winter. While treatment usually involves medication and lifestyle changes, surgical treatment can be performed in young animals to attempt place the head of the femur more tightly within the hip, but this treatment is of no use to the adult animal with arthritic pain. In smaller animals, removing the head of the femur may relieve pain, but larger animals (who more commonly develop this condition) usually do not cope well with this type of surgery. Total hip replacement is generally considered the surgical procedure of choice in the larger patient.

All breeding animals should consider undergoing a recognised screening program with a registry in your country (e.g. Penn Hip). This means that the amount of abnormality in the hip joint is measured in a consistent manner from dog to dog. The hip dysplasia itself is present in affected dogs from a young age, and screening is usually carried out at 12 months up to 2 years of age. Screening at a younger age (4-5 months) allows for possible surgery to be carried out with the aim of correcting any looseness in the hips. However many registries (e.g. the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals, or OFA) will only certify dogs that are x-rayed at 1 - 2 years of age.

|

||

|

Progressive Retinal Atrophy - Central (cPRA) |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. Retinal examination by veterinary ophthalmologist (Recommended at age 2, 3, 4 and 5 years)

Overview

This is a disorder of the pigmented epithelium of the retina, which results in progressive retinal degeneration. The retina is responsible for detecting and processing light, and turning it into signals that travel to the brain to be processed into vision. As the retina progressively degenerates, vision is progressively lost. Central PRA is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait (with variable penetrance) in the Labrador, Border collie and Shetland sheepdog, and as an autosomal recessive defect in the English springer spaniel, golden retriever and Irish setter. It is more commonly seen in the UK, and other predisposed breeds include the boxer, Cardigan Welsh corgi, collie, English cocker spaniel, German shepherd dog, pointer, English setter and Chesapeake Bay retriever. Initially, dogs develop problems with day vision, in the centre of their field of vision (hence the name central PRA). Peripheral vision will initially remain intact. This central loss of vision gradually gets worse, and eventually it can (although not always) lead to total blindness. Vision problems usually start between 1.5 and 3.5 years of age. Late stage disease cannot be distinguished from generalised PRA on ophthalmic examination. The electroretinogram (ERG) remains normal until late in the course of the disease, unlike generalised PRA, where it can detect early disease. There is no DNA test for this disease, and affected animals should not be used for breeding. |

||

|

Progressive Retinal Atrophy - Progressive Rod Cone Degeneration (prcd-PRA) |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. DNA testing of all breeding animals prior to entering into a breeding program (e.g. at 1 year old)

2. Examination by specialist veterinary ophthalmologist at puppy eye exam and then annually from 1 year of age

Overview

Progressive retinal atrophy (PRA) is a collection of inherited diseases affecting the retina that cause blindness. Each breed exhibits a specific age of onset and pattern of inheritance, and the actual mechanism by which the retina loses function can vary. The result of almost all types of PRA is similar - generally an initial night blindness, with a slow deterioration of vision until the dog is completely blind. The age at which the dog becomes fully blind also varies, depending on the genetic disruption present and the breed. Affected eyes are not painful, unless complicated by a secondary problem, such as cataract or uveitis (inflammation due to a leaking cataract).

Progressive retinal atrophy (PRA) has been classified in several different ways. The simplest of these is by age of onset. Early onset PRA occurs when the affected dog is night blind from shortly after birth, and generally is completely blind between 1 - 5 years of age. Late onset PRA is where the dog is night blind at some time over 1 year of age, and full blindness will occur at a somewhat later stage in life.

Another is by the type of genetic abnormality causing the PRA. PRA may be inherited by recessive, dominant or sex-linked mechanisms in dogs. For many types of PRA in many breeds a DNA test is now available to allow for easy screening for the disease. Despite the complexity of the disease and its many forms, ultimately all forms have one thing in common – degeneration of the retina causing progressive loss of vision.

DNA tests are not yet available for all affected breeds. And because breeds may also be prone to several forms of PRA (and not all may have a genetic test available) examination of the retina by a veterinary ophthalmologist remains a mainstay of the diagnostic testing regimen. In some breeds with a late onset PRA, serial eye examinations may be required before the signs of retinal degeneration become apparent. Electroretinography (ERG) is a diagnostic test that the veterinary ophthalmologist may choose to use in some cases and is a very sensitive method of detecting loss of photoreceptor function. The ERG can be a very good screening test for puppies that may have an early onset form of PRA.

In progressive rod cone degeneration (known as prcd-PRA) photoreceptors of the retina appear to develop normally, then develop irregularities and progressively lose function. A mutation has been discovered on a gene called PRCD, and this mutation seems to be responsible for this condition in at least 40 breeds, when a dog possesses two copies of the mutation. This is therefore an autosomal recessive mutation, and a DNA test is available. The same mutation has been found to cause retinitis pigmentosa in people.

The age of onset of retinal changes varies depending on the breed. Clinical signs may be seen from as early as 2 years of age in the golden retriever or may not be clinically apparent until 3-5 years of age, as in miniature and toy poodles. (Hence it is a late onset form of PRA.) Some cocker spaniels are even older than this when clinical signs are first seen.

Initially the disease will manifest as night blindness, but will slowly progress to blindness in bright light. Serial eye exams are required to detect the early signs of PRA. Often cataracts can develop concurrently, and this may lead to uveitis or glaucoma, which can certainly be painful and needs to be treated appropriately.

Dogs generally adapt quite well to blindness - especially when it develops gradually - as long as their surroundings remain familiar (e.g. furniture does not get rearranged, they do not move house etc). They should always be kept on a lead outside the yard, and care should be taken not to startle them. Balls containing bells (as an example) can be used as toys for mental stimulation.` |

||

|

Retinal Dysplasia (Oculoskeletal Dysplasia) |

No prevalence data is currently available

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. Eye examination by veterinary ophthalmologist at puppy eye exam (12 - 16 weeks of age)

2. DNA test for all breeding animals prior to entering into a breeding program (e.g. at 1 year old)

Overview

The retina is comprised of several layers of tissue at the back of the eye that includes and supports the photoreceptors that detect light. Retinal dysplasia (RD) occurs when the two layers of the retina do not form together properly, resulting in folds or rosettes of lifted tissue. This disease may be so mild as to be clinically inapparent, or if the disorder is severe, blindness is the result due to complete retinal detachment from the underlying retinal pigmented epithelium.

In certain breeds retinal dysplasia occurs due to a specific collagen defect, and is seen together with skeletal abnormalities. In the Labrador retriever (and breeds derived from it) a mutation in the COL9A3 gene causes oculoskeletal dysplasia 1 (OSD1), while in the Samoyed a mutation in the COL9A2 gene leads to oculoskeletal dysplasia 2 (OSD2). Both diseases cause mild retinal changes in the heterozygote state, with severe retinal dysplasia causing blindness and chondrodysplastic dwarfism in homozygotes. The disease can be detected in homozygotes (i.e. those with two copies of the mutated gene) from around 4-6 weeks of age, with skeletal changes including a domed skull and shortened limbs, especially forelimbs which take on a bowed look. These pups also have abnormalities of the vitreous and lens of the eye, as well as frequent complete retinal detachment, seen on eye examination as early as 6 weeks of age.

In those animals with one copy of the abnormal gene (i.e. heterozygotes) by contrast, skeletal development is always normal, and so the osteochondrodysplasia is described as "recessive in nature". However a number of heterozygote dogs (but not all) will have visible retinal folds on ocular examination at 12 - 16 weeks of age, and some will have vitreal abnormalities. None have retinal detachment or cataracts. Some dogs have a normal eye examination. Hence retinal dysplasia is described as "incompletely dominant", or "dominant with incomplete penetrance" or "variable expression".

If two dogs with one copy of this gene are bred, even if they do not both have eye abnormalities, they will produce some pups who have two copies of the mutation that causes the disease, and will therefore have skeletal changes and blindness. This is why it is important to screen for oculoskeletal dysplasia (OSD) in breeding animals, and avoid breeding two carrier animals together. Note that any animal of an affected breed found to have retinal folds on eye exam should also be tested for this potentially devastating disease before entering a breeding program. |

||

|

Tricuspid Valve Dysplasia |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. Auscultation at each puppy veterinary examination.

2. Echocardiography in any puppy with a persistent cardiac murmur (present at 2nd and/or 3rd puppy visit) Overview

This is a congenital heart condition that is common in a number of breeds, and is the most common congenital heart condition in the Labrador retriever. In the Labrador it is thought to be inherited with a dominant mode of inheritance, while in other breeds the mode of inheritance is still unknown.

The tricuspid valve is located in the right side of the heart, and sits between the ventricle and the atrium. When the heart contracts, the normal tricuspid valve closes and stops blood flowing backwards into the atrium. With tricuspid valve dysplasia, the valve has not formed properly, and it allows blood to leak backwards through it when the heart contracts. This causes a murmur, and leads to heart enlargement, and eventually right-sided congestive heart failure.

Puppies may be diagnosed with tricuspid valve dysplasia due to investigation of a persistent heart murmur detected at vaccination, and an echocardiogram (heart ultrasound) will allow detection of the abnormality. Sometimes the murmur may go undetected at this time, but an echocardiogram will still visualise the problem.

The age at which signs of heart failure appear can vary, depending on the severity of the valve abnormality that is present. A few dogs may have small defects in the valve that never lead to heart failure. Most will develop clinical signs as time goes on. There may be decreased exercise tolerance and cool extremities due to poor peripheral circulation. Signs commonly seen involve fluid build up in body cavities (especially the abdomen), rapid breathing, weakness and exercise intolerance. Abnormal heart rhythms are common, and can cause a very rapid heart rate in some cases.

Treatment aims to manage signs of congestive heart failure, however, once signs become apparent, dogs usually die fairly soon after, and the average life expectancy of a dog with tricuspid valve dysplasia is 1 – 3 years. There is no cure, and affected animals should not be used for breeding. |

||

These conditions are reported to have a breed predilection in the Mixed Breed, although they are less common than those mentioned earlier, or have less of an impact on the animal when they occur. Hence they are not covered in detail in this article, however further information can be found by clicking on any diseases that are highlited. This list is not a comprehensive list of all diseases Labrador Retriever may be prone to.